Our modern lifestyle is often blamed for the explosion in conditions like asthma, diabetes and obesity - but the evidence that our predecessors didn't suffer such ailments has been hard to come by - until now.

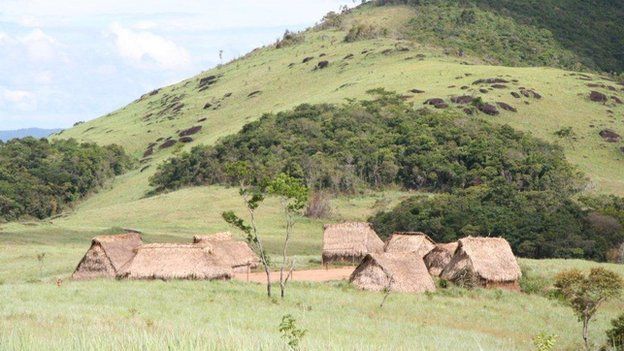

In 2008 a military helicopter chanced upon a previously uncharted group of huts in the remote Amazonas region in southern Venezuela, home to 15,000 Yanomami people.

Thought to have been completely isolated since their ancestors arrived in South America after the last ice age, the semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers have never been exposed to wider civilisation - therefore neither have their guts.

The community hunts for small birds and mammals as well as frogs and fish and the occasional tapir. They also eat wild bananas, plantain and cassava.

Water is collected from a stream about five minutes' walking distance from the village.

An international team of scientists has studied the group - whose exact location has been protected - to see what micro-organisms (microbes) lived in and on them.

Some microbes cause disease; the majority are completely harmless but humans couldn't live without them.

The microbes we are born with - which mainly come from our mother's birth canal - form the basis of our lifelong microbiome.

We are literally covered in them, inside and out. But developments in lifestyle can alter the microbial composition.

The use of antibiotics, processed foods and soap may have led to less diversity in our microbes according to Dr Gautam Dantas from the Washington University School of Medicine, one of the researchers who has studied the Yanomami people.

Restore the balance?

Dr Dantas, whose work is published in Microbial Ecology, says it seems a reasonable hypothesis to relate this behaviour to an increase in "newer" diseases like asthma, inflammatory bowel disease and diabetes

Maria-Gloria Dominguez-Bello from the New York University School of Medicine has analysed microbes from this group and compared them with Western people's.

Dr Dominguez-Bello believes infancy is an important "window" for the immune system to be primed, when it can learn which are the good microbes and which ones to fight off.

She says American infants have, on average, two courses of antibiotics in the first year of life - and one in three of those children will have been delivered by Caesarean section - one in two if they happen to be born in Brazil.

Dr Dominguez-Bello says: "If you upset the good bacteria, it might well be that the immune system of that baby will be ill-educated and respond wrongly to other agents and bacteria."

The Yanomami people agreed to have the microbes in their mouths, on their skin and in their faeces analysed by the international research team.

Dr Dominguez-Bellow was surprised by some of the findings - the microbes from their skin and gut were 40% more diverse than those of urbanised people.

"In the intestine they have a diversity that really shocked us, which we think are providing a lot of important roles in digestion and in communicating with our immune system.

"We want to understand what are the bacteria that we have lost and what were their functions - and can we restore them eventually?"

In contrast, the microbes found in the mouths of the Yanomami had a similar balance to those of Western urban dwellers, something researchers think could result from their habit of chewing tobacco - a mild antiseptic - from an early age.

Antibiotic resistance

One other surprising finding was that the microbes from the Yanomami have antibiotic resistance genes despite never having encountered modern antibiotics - although they are not "switched on".

Dr Dantas said they found half a dozen resistance genes. He said: "Antibiotic resistance is a natural feature of bacteria in the human body. It's not something created by antibiotic use. But it does get amplified when antibiotics are used."

This "baseline" microbiome from the isolated Yanomami has also been compared with other hunter-gatherers from Malawi, as well as Guahibo Amerindians, who are already moving towards urban living with access to medical care and changing agricultural practices.

It was found that the more exposed a group was to these lifestyle developments, the less diverse the microbiome.

He says more research is now needed to understand the role of these resistance genes - to understand the effect on the immune system and metabolism.

And once we know, could we simply "top up" our microbes to reduce the impact of such developments?

Dr Dantas believes that there will be a commercial interest in "bioprospecting" or developing synthetic compounds to modulate these effects.

But he still believes we have a responsibility to reduce our antibiotic use - and maybe not to be so obsessed with cleanliness.

"I found my two-year-old tucking into some hay and manure which my parents have delivered to my home for the garden.

"I'm hoping the bacterial load had dropped as it dried out."

No comments:

Post a Comment